All of us are drowning in an ocean of media.

Impressions are a false currency.

We collaborate with brands that understand that interruptive advertising and social trend-chasing are an inefficient way to build affinity and earn trust from an audience.

We plan, produce and distribute branded entertainment: Films, Shorts, Podcasts, Activations, Games, Zines.

Anything we can dream up together.

Don't interrupt what people enjoy.

Be what people enjoy.

A CASE FOR INVESTING IN branded entertainment

In Ogilvy on Advertising (1983), David Ogilvy shares a story that rarely makes it into conference decks:

George Hay Brown, then head of marketing research at Ford, ran an experiment inserting ads into every other copy of Reader’s Digest. A year later, those who hadn’t seen the ads bought more Fords.

Four decades later, the industry still struggles to admit that advertising can backfire. There’s little incentive to scrutinize the damage. Even in the age of performance marketing — the 2010s wave of cheap, hyper-targeted digital ads — we saw direct-to-consumer brands rise fast on conversion-driven tactics, then collapse just as quickly when the funding dried up.

The C-suite is starting to respect brand again. Marketing effectiveness studies and case studies have slowly moved the conversation beyond the tired “brand vs. performance” binary. But if we’re going to talk about long-term brand building, we have to talk honestly about advertising — not just how it helps, but how it can hurt.

Here’s the problem:

Most ads never reach the right audience.

Even when they do, they’re ignored.

Even when they’re not, they’re forgotten.

Even when they’re remembered, they’re annoying.

Does that make advertising worthless? No. Just inefficient.

About 5% of an audience is in-market at any given time — and those people will notice category ads more. That’s why a well-timed, well-crafted ad can help move a product into the consideration set.

But for brand building, advertising behaves like a pickup line at a bar. It might work, if the person delivering it has charisma, timing, and a killer line. Otherwise, it’s just an interruption. And most people are just trying to do jello shots and forget the crushing weight of late capitalism.

Imagine the commercial break never existed. Now imagine pitching it to a modern CMO — “Let’s interrupt people mid-content with a message they didn’t ask for.”

The obvious question: Wouldn’t that just make them hate us?

And yes, the industry still makes these kinds of ads. We do too. Sometimes interruptive advertising is the only way to be seen. Business is imperfect. Visibility matters.

But whenever there’s buy-in for a better way, smart brands take it.

Branded entertainment takes more effort, but brings less risk of negative salience and much higher upside. It’s a positive attention exchange — a film, a series, a game, a podcast, a zine — content that people choose to engage with, not tolerate.

It doesn’t chase. It attracts. Less like a pickup artist, more like the person who goes to therapy, volunteers at the community garden, and radiates a sense of purpose.

Yes, ads can be entertaining too. But the difference is consent — and cultural value. Are you participating in culture, or interrupting it?

The returns on branded entertainment are slower to measure, but harder to ignore. They compound. They endure.

Go Deeper (PDF)

George Hay Brown, then head of marketing research at Ford, ran an experiment inserting ads into every other copy of Reader’s Digest. A year later, those who hadn’t seen the ads bought more Fords.

Four decades later, the industry still struggles to admit that advertising can backfire. There’s little incentive to scrutinize the damage. Even in the age of performance marketing — the 2010s wave of cheap, hyper-targeted digital ads — we saw direct-to-consumer brands rise fast on conversion-driven tactics, then collapse just as quickly when the funding dried up.

The C-suite is starting to respect brand again. Marketing effectiveness studies and case studies have slowly moved the conversation beyond the tired “brand vs. performance” binary. But if we’re going to talk about long-term brand building, we have to talk honestly about advertising — not just how it helps, but how it can hurt.

Here’s the problem:

Most ads never reach the right audience.

Even when they do, they’re ignored.

Even when they’re not, they’re forgotten.

Even when they’re remembered, they’re annoying.

Does that make advertising worthless? No. Just inefficient.

About 5% of an audience is in-market at any given time — and those people will notice category ads more. That’s why a well-timed, well-crafted ad can help move a product into the consideration set.

But for brand building, advertising behaves like a pickup line at a bar. It might work, if the person delivering it has charisma, timing, and a killer line. Otherwise, it’s just an interruption. And most people are just trying to do jello shots and forget the crushing weight of late capitalism.

Imagine the commercial break never existed. Now imagine pitching it to a modern CMO — “Let’s interrupt people mid-content with a message they didn’t ask for.”

The obvious question: Wouldn’t that just make them hate us?

And yes, the industry still makes these kinds of ads. We do too. Sometimes interruptive advertising is the only way to be seen. Business is imperfect. Visibility matters.

But whenever there’s buy-in for a better way, smart brands take it.

Branded entertainment takes more effort, but brings less risk of negative salience and much higher upside. It’s a positive attention exchange — a film, a series, a game, a podcast, a zine — content that people choose to engage with, not tolerate.

It doesn’t chase. It attracts. Less like a pickup artist, more like the person who goes to therapy, volunteers at the community garden, and radiates a sense of purpose.

Yes, ads can be entertaining too. But the difference is consent — and cultural value. Are you participating in culture, or interrupting it?

The returns on branded entertainment are slower to measure, but harder to ignore. They compound. They endure.

Go Deeper (PDF)

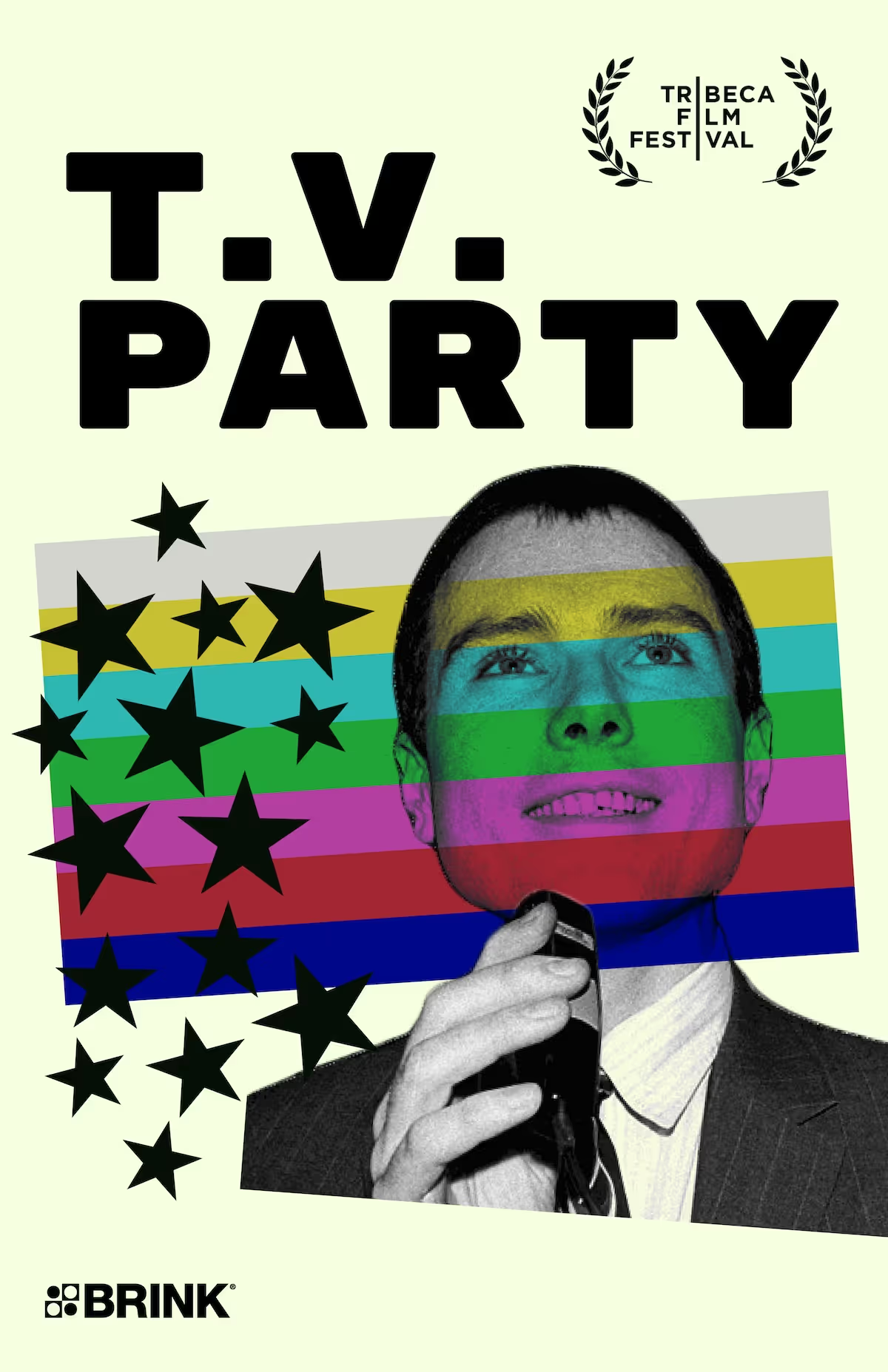

some OF OUR BRANDED ENTERTAINMENT WORK

FEATURE FILMS

We also produce films that have screened at major festivals (Sundance, Tribeca, SxSW, TIFF) and received wide distribution including theatrical release.